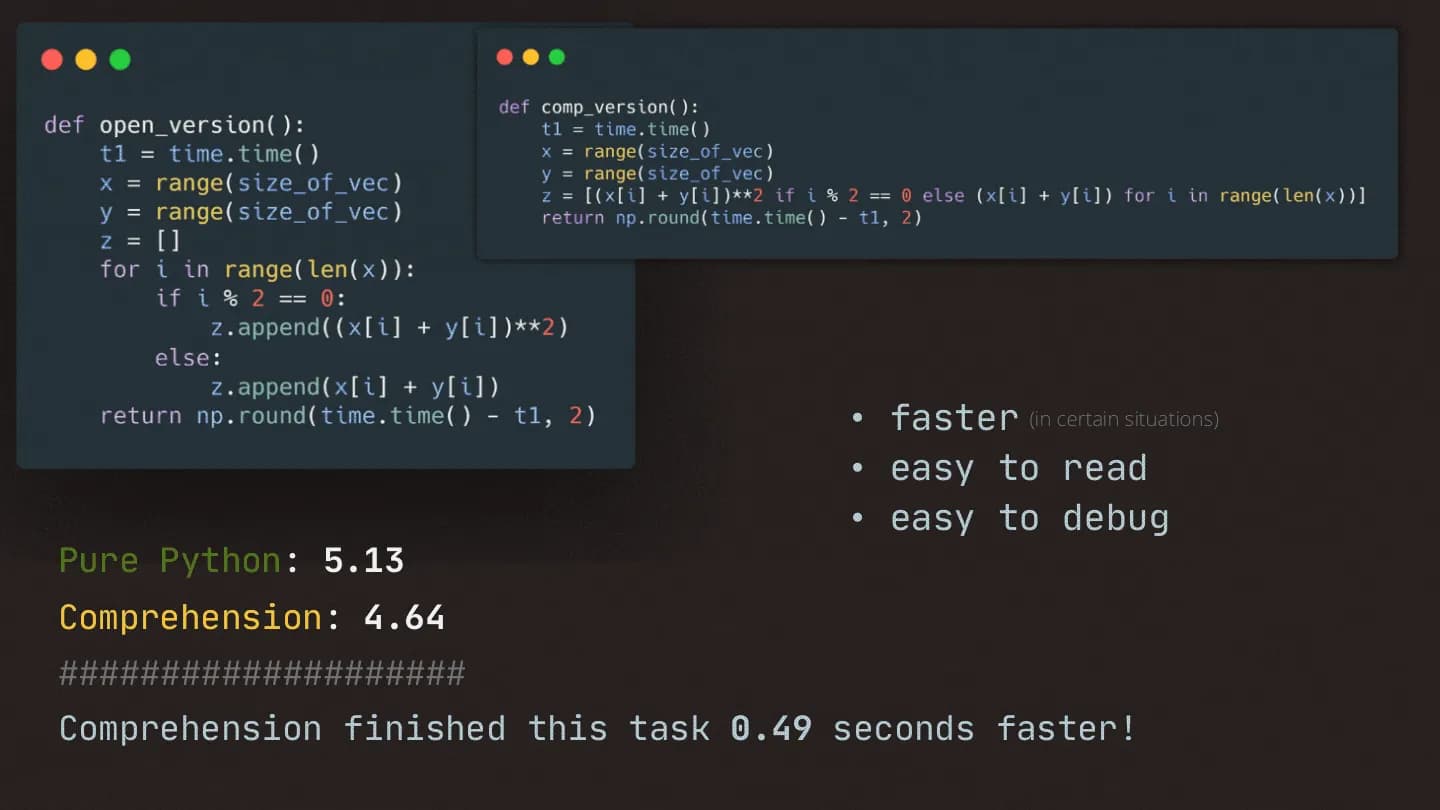

List comprehensions are an elegant way to define and create lists based on existing lists. It might seem like this same output can be achieved using a simple for loop. Then why would we want to use a list comprehension?

- List comprehensions are generally more compact and faster than normal functions and loops for creating a list.

- They are easier to read and debug if they are properly used. We should avoid writing very long list comprehensions in one line to ensure that code is user-friendly.

The Basics

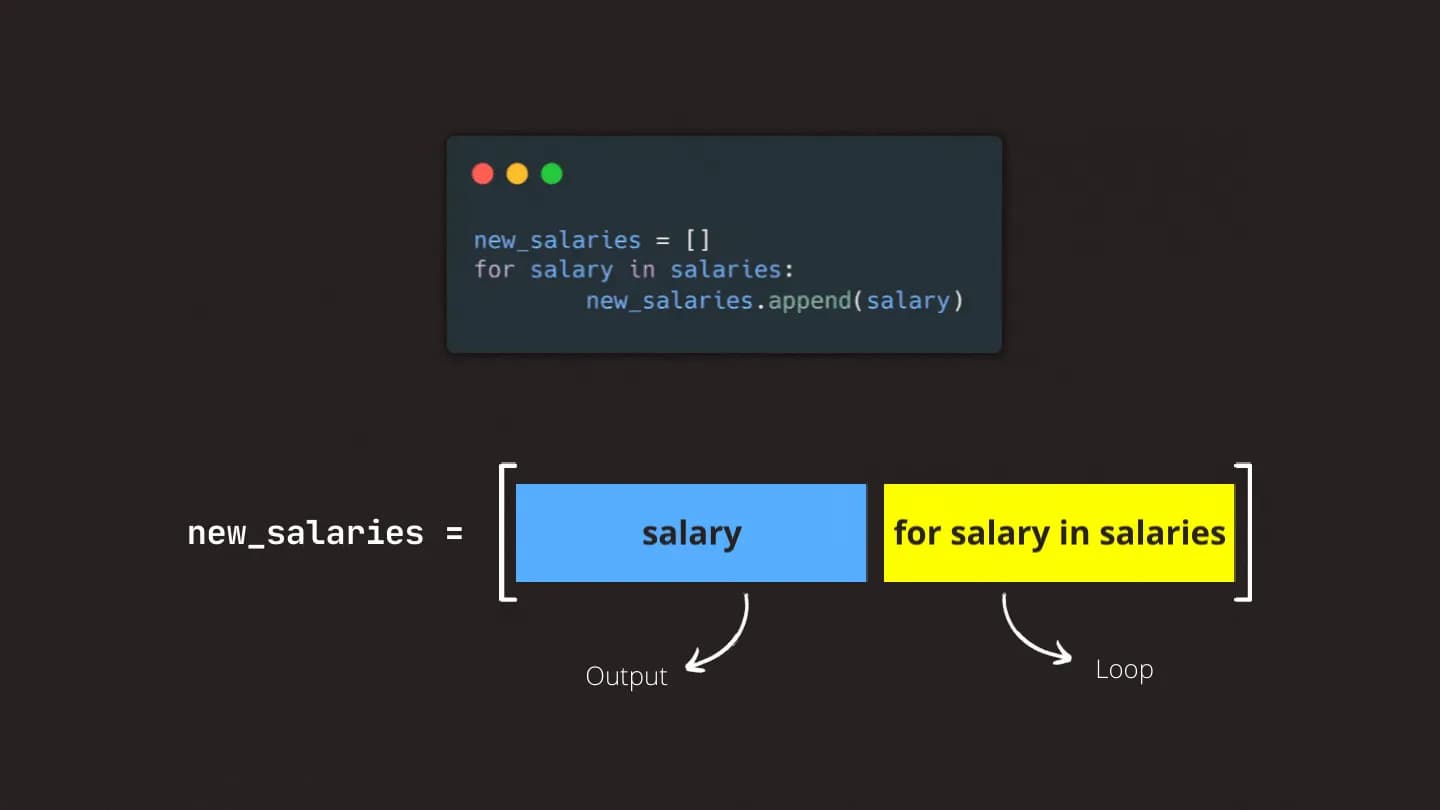

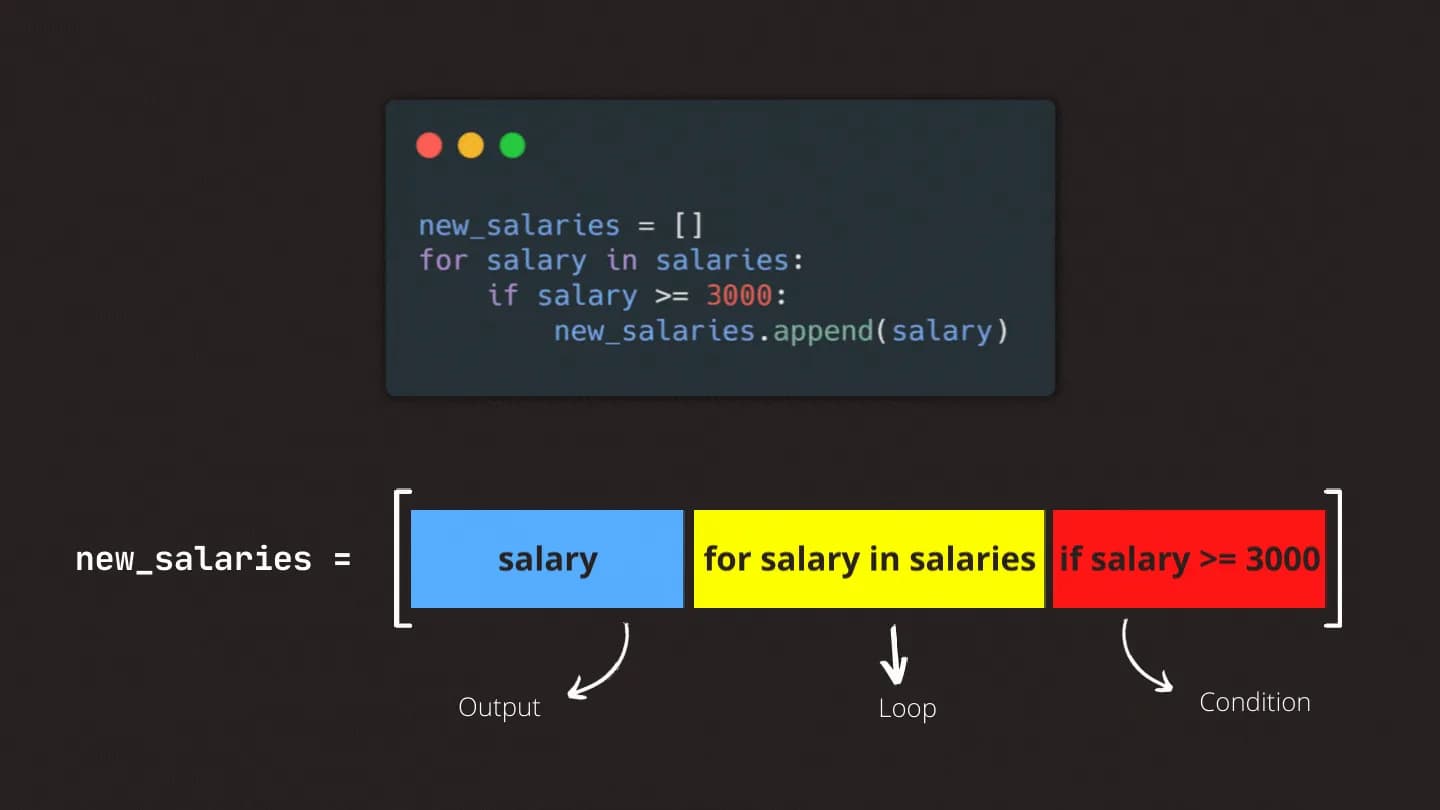

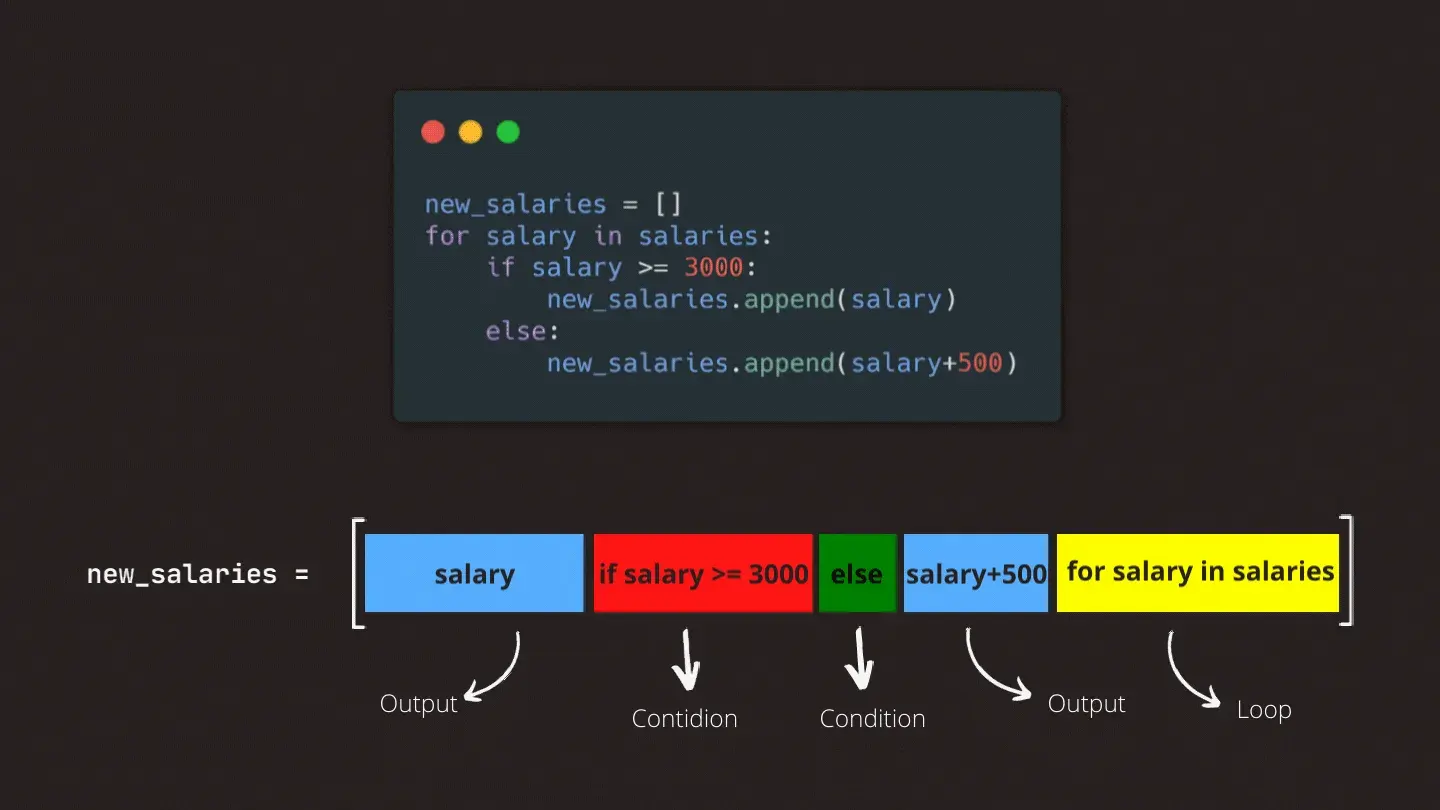

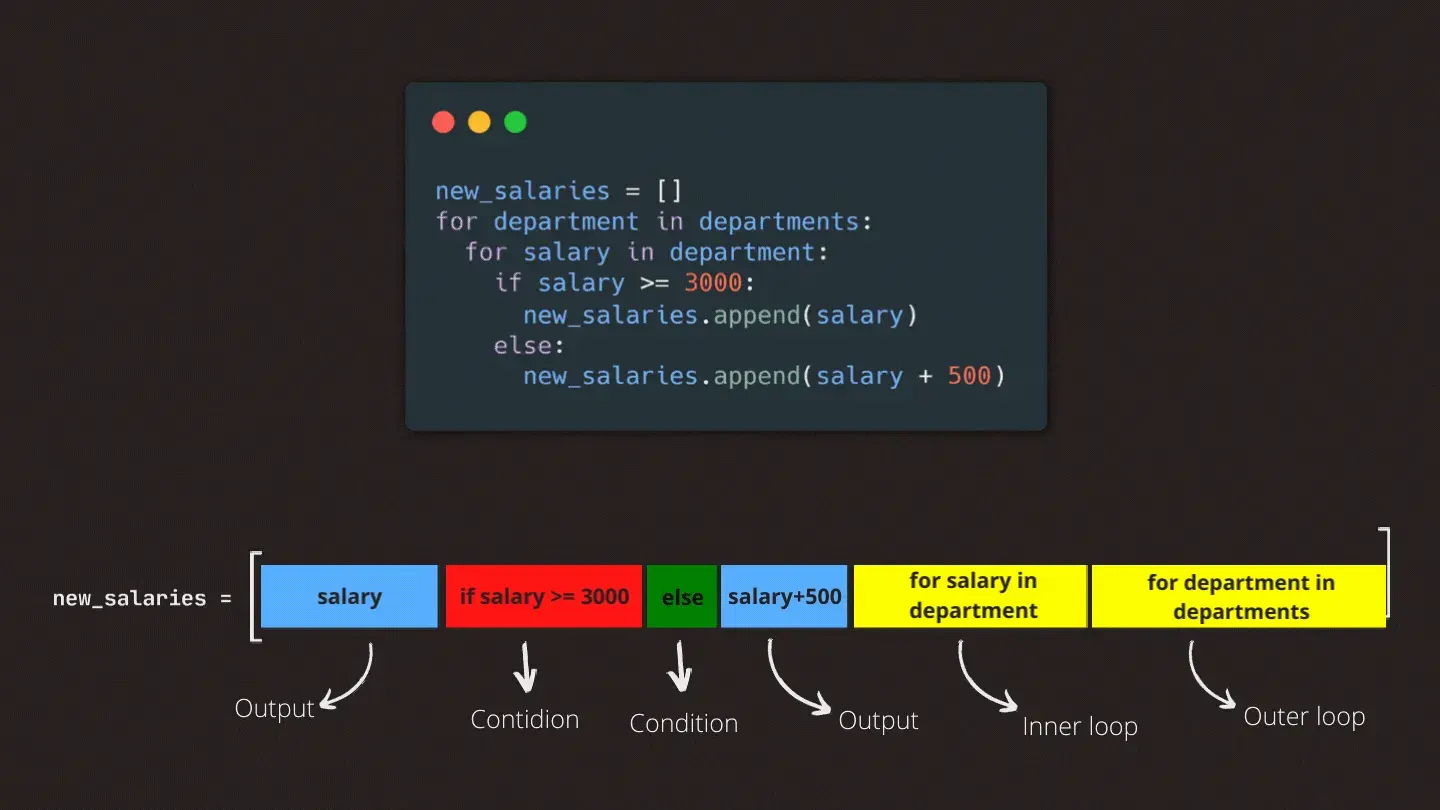

Now let’s dive into how we can use them. I color-coded the important parts to make it easier to see how we can get the same result as a regular for loop using list comprehensions.

- Blue: The output you want to have in your list

- Yellow: for loops to go through every element in iterative objects.

- Red: if statements.

- Green: else statements.

new_salaries = []

for salary in salaries:

new_salaries.append(salary)

# becomes

new_salaries = [salary for salary in salaries]The two expressions above will give us the same result. It will go through every element in the salaries list and add them to a new list called new_salaries. Using list comprehensions on this example allowed us to accomplish the same task writing only a one-line, easily-readable code.

Conditional Logic

To use conditional logic with list comprehensions there are some differences in syntax depending on what we want to accomplish. If we are going to use an if condition only, we can add the expression just after the loop part of the comprehension. In this example, we are adding salaries equal to or higher than 3000 to our new list.

new_salaries = []

for salary in salaries:

if salary >= 3000:

new_salaries.append(salary)

# becomes

new_salaries = [salary for salary in salaries if salary >= 3000]If we want to use an else statement in our comprehension, the syntax differs a bit. In this situation, we first state the output we want from our if statement, followed by the statement itself, then we add our else statement followed by the output we want to get from our else statement. And lastly, we add our for loop to the end of our list. In this example, we leave salaries equal to or higher than 3000 just as they are, and we’re giving a 500 raise to the rest.

new_salaries = []

for salary in salaries:

if salary >= 3000:

new_salaries.append(salary)

else:

new_salaries.append(salary + 500)

# becomes

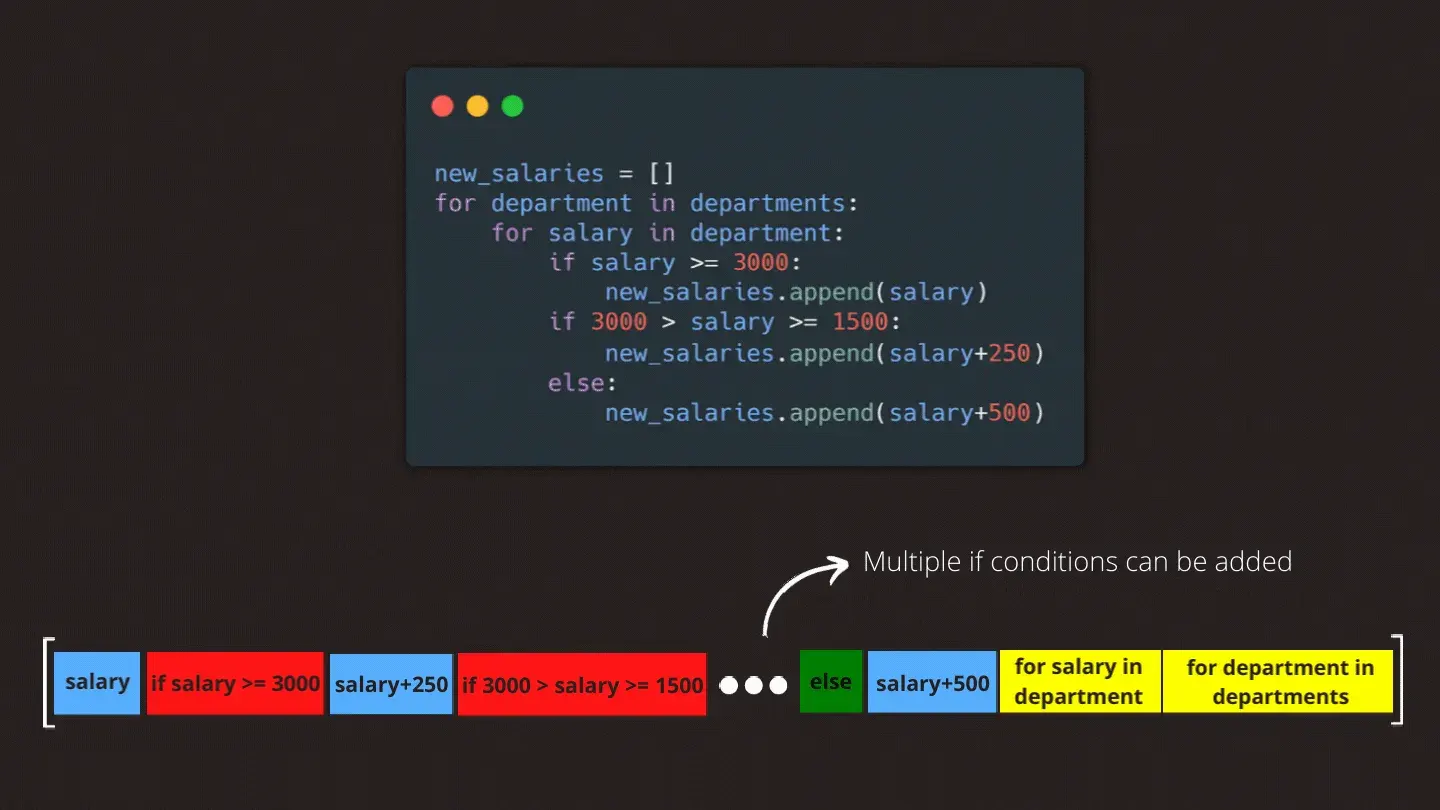

new_salaries = [salary if salary >= 3000 else salary + 500 for salary in salaries]We can add multiple if conditions one after another in list comprehensions. But it doesn’t mean we should. One of the main points of using list comprehensions is their readability.

Nested Loops

Let’s imagine we were working on a single department this whole time. Now we have to get working on other departments too. Now we have a list of lists called departments and in every element of departments, we have salaries of a certain department. If we want to access the salaries we have to go by order. First, we select a department, then go through every salary in that department and calculate new salaries depending on the current salaries.

new_salaries = []

for department in departments:

for salary in department:

if salary >= 3000:

new_salaries.append(salary)

else:

new_salaries.append(salary + 500)

# becomes

new_salaries = [

salary

if salary >= 3000

else salary + 500

for salary in department

for department in departments

]Caveats

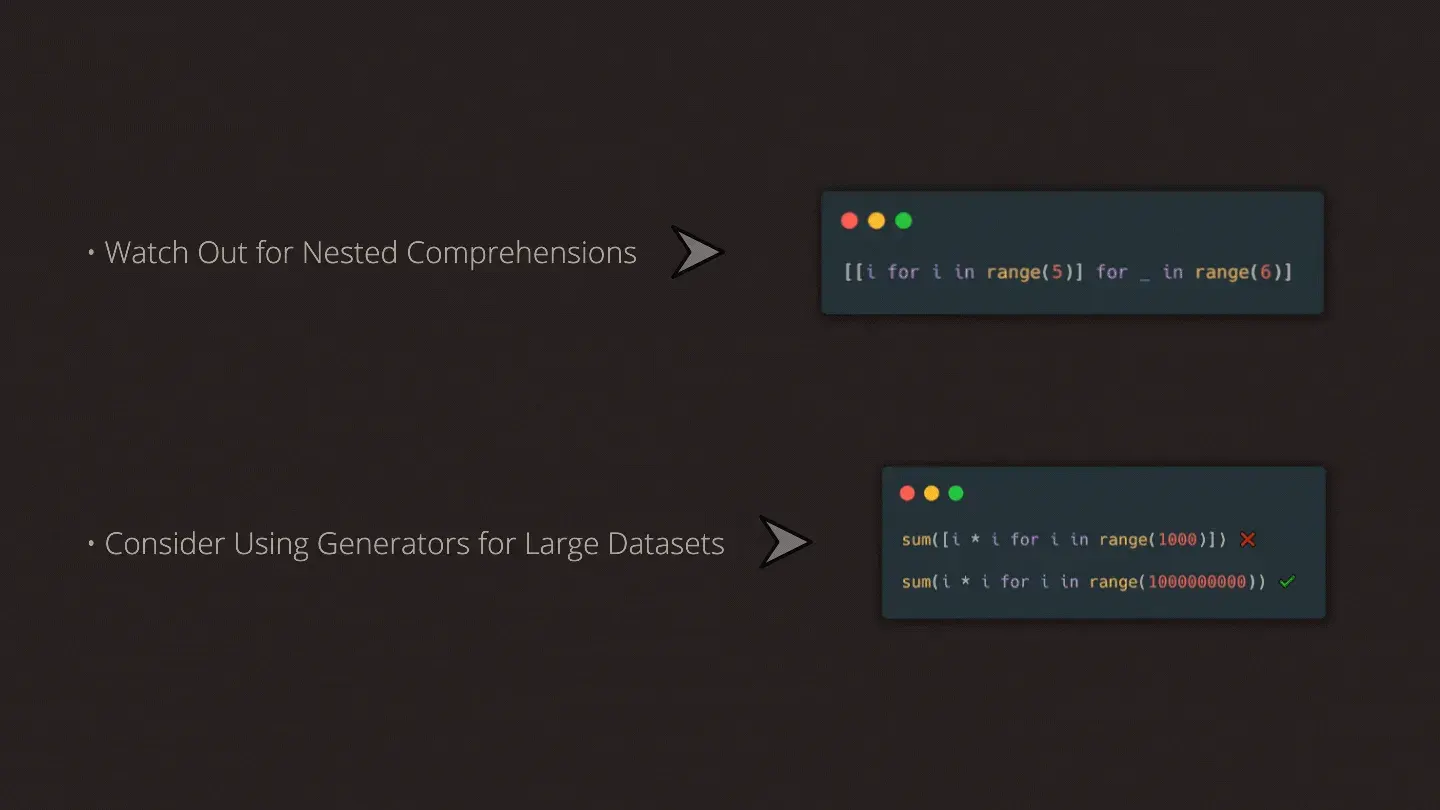

The main point of using list comprehensions is producing readable code. We should avoid using very long list comprehensions. Remember that every list comprehension can be rewritten in for loop, but every for loop can’t be rewritten in the form of list comprehension. Be careful using list comprehensions for nested loops. What’s most important is to write code that can easily be read and modified.

We went through what are list comprehensions, why and when they are useful, and how to use them. But there are some caveats we should consider when we decide to use them.

While working with large datasets consider using generators instead of comprehensions. A generator doesn’t create a single, large data structure in memory, but instead returns an iterable. Your code can ask for the next value from the iterable as many times as necessary or until you’ve reached the end of your sequence, while only storing a single value at a time.